Total Pageviews

Tuesday, 14 April 2020

How to convert a PDF to EPUB

from Digital Trends https://ift.tt/2eWwKeA

via IFTTT

The best Google Chrome themes for 2020

from Digital Trends https://ift.tt/2vfkPjP

via IFTTT

The best tax software for filing your taxes in 2020

from Digital Trends https://ift.tt/2ECmJ2f

via IFTTT

The best chat clients for 2020

from Digital Trends https://ift.tt/2p8VnVW

via IFTTT

Coronavirus and pets: How does COVID-19 affect cats and dogs? - CNET

from CNET https://ift.tt/3ent5ky

via IFTTT

Twitter's Jack Dorsey pledges $1B to coronavirus relief, $2.1M to related domestic violence - CNET

from CNET https://ift.tt/3clPIE9

via IFTTT

How to manage a pandemic

My first taste of coronavirus panic came early one morning in January. An email with the heading important information please read arrived from our son’s elementary school, just minutes before we put him on the bus. The parents of one of his teachers, who had recently returned from China, had been infected—Singapore’s cases 8 and 9, as it turned out—and the teacher in question was being quarantined.

Singapore was among the first countries to suffer an outbreak. In the months since, it has been at once reassuring and unnerving to watch its journey from an early hot spot to a kind of haven state, holding out doggedly against an invader that has infiltrated so many others.

Early commentary in the West focused on the failings of China’s autocratic system, which hid the severity of Wuhan’s outbreak—at what we now know to be catastrophic cost. The more the epidemic has spread, the more it has become clear that Western liberal democracies have badly mishandled it too, ending up with severe outbreaks that could—perhaps—have been avoided.

You can read our most essential coverage of the coronavirus/covid-19 outbreak for free, and also sign up for our coronavirus newsletter. But please consider subscribing to support our nonprofit journalism.

Yet it makes little sense to view the coronavirus as some kind of perverse vitality test for liberal and authoritarian regimes. Instead we should learn from the countries that responded more effectively—namely, Asia’s advanced technocratic democracies, the group once known as the “Asian Tigers.” In the West the virus exposed creaking public services and political division. But Hong Kong, Japan, and South Korea have managed better, while Singapore and Taiwan have kept the disease almost entirely under control, at least for now.

Lessons learned

Partly this shows the benefits of experience. The Asian “technocracies,” as geopolitical thinker Parag Khanna dubs them, all suffered SARS outbreaks beginning in 2002, as well as more recent minor scares, such as H1N1 in 2009. These experiences, bruising at the time, helped government planners think through contingencies, developing outbreak management plans and stockpiling essential goods. Taiwan accumulated millions of surgical masks, coveralls, and N95 respirators for medical staff, and kept tens of millions more for the public.

“Your test is positive. The ambulance will arrive there in 20 minutes. Pack your stuff.”

It was also thanks in part to SARS that Asian countries understood the need for rapid action, as Leo Yee Sin, head of the NCID, noted back in early January. At that point, covid-19 was still being referred to as a “mystery pneumonia.” Around the region, passengers on flights from affected parts of China were given mandatory temperature checks. As the crisis deepened, those flights were canceled, and then borders were closed entirely. Not every country followed quite the same model of response: Hong Kong and Japan shut their schools early, while Singapore kept its open. But all acted quickly, in coordinated responses led by experts.

There were new treatment centers too, including Singapore’s National Centre for Infectious Diseases (NCID), a 330-bed facility opened just last year, which stands a 10-minute drive from my office. A friend—Singapore’s case 113—ended up there for weeks in March, having caught the virus on a trip to Europe and begun to feel symptoms on his flight back home. He was first taken to the center for a test—“The scene was pretty post-apocalyptic, with everyone in plastic suits with big goggles and masks, in rooms filled with plastic partitions”—but was sent home to isolate and await results. He got a call back a few hours later. “They told me, ‘Your test is positive,’” he remembered, while still in isolation at the center in late March. “The ambulance will arrive there in 20 minutes. Pack your stuff.”

Technology mattered too. China deployed extensive and invasive surveillance to bring the virus’s spread under control, pushing tech giants to track and monitor hundreds of millions of citizens. New apps proliferated, notably the Alipay Health Code, which assigned users a rating of green, yellow, or red, based on their personal health records with the company. The app, which shared information with Chinese police and other authorities, in effect decided who was quarantined at home and who was not.

Asia’s democracies often took more basic routes, monitoring and managing the outbreak with tools no more advanced than phones, maps, and databases. Singapore in particular rolled out an admired contact tracing system, in which centralized teams of civil servants tracked down and contacted those who might have been affected. Their calls could be shocking. One minute you were oblivious at work; the next minute the Ministry of Health was on the phone, politely informing you that a few days before you had been in a taxi with a driver who subsequently fell ill, or sitting next to an infected diner at a restaurant. Anyone getting such a call was sternly instructed to sprint home and self-isolate.

What made this possible was that anyone infected could be grilled for hours. “They sat me down and interrogated me about my travel: every day, minute by minute,” my friend told me. “Where did I go? Which taxi did I take? Who was I with? For how long?” The process of tracking and tracing was laborious but produced impressive results. Nearly half of the roughly 250 people infected in Singapore by mid-March first learned that they were at risk when someone from the government called and told them.

Just as efficient was South Korea’s testing regime, which in January forced local medical companies to work together to develop new kits and then rolled them out aggressively, allowing planners to keep track of the pandemic’s spread. South Korea had tested about 300,000 people by late March, roughly as many as the United States had managed by then, but in a country with a population one-sixth as large.

Clear communication

Transparency was another factor, though perhaps a less expected one in Asia’s more autocratic societies. True, media coverage early on was more muted and respectful in countries like Japan and Singapore than in places like the UK, where aggressive reporting highlighted all manner of details that public authorities might have preferred to play down, such as contingency plans to open up a morgue in London’s Hyde Park.

Nonetheless, open communication from governments has been a consistent pattern in Asia’s more successful responses. Singapore put prominent front-page advertisements in the media, including early campaigns to try to stop citizens with no symptoms from buying up surgical masks and causing shortages for those who needed them. Taiwan and South Korea provided reliable and open data to citizens, along with regular social-media briefings.

As the pandemic worsened, I took a trip to the United States, sure to be the last for quite some time—departing through the forests of temperature checks and body heat scanners that by then lined the corridors of Changi Airport.

For the week I was away, I got calmly factual updates pinged to my phone roughly three times a day from the Singaporean government via WhatsApp, giving details about new infections and what the authorities were doing in response.

This focus on open information was another lesson taken from earlier crises. During the SARS crisis, as well as the 2015 outbreak of Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS), administrations in countries like South Korea were criticized for hiding information and damaging public trust. This time they appear to have concluded that frequent updates from politicians and health experts were a more effective technique against viral misinformation.

This is not to pretend that everything has been perfect. Japan messed up its response to the arrival of the Diamond Princess cruise ship in Yokohama, and—like the US—has faced persistent questions since about its own lack of testing equipment.

Hong Kong’s government was widely criticized too, in the aftermath of recent street protests that badly eroded public confidence. Hong Kong’s citizens, however, have shown extraordinary willingness to self-isolate—which may in part be because they distrust the state’s ability to solve the crisis, not because they meekly follow government orders.

Indeed, the examples of Hong Kong and Taiwan, itself a rambunctious democracy, give the lie to the notion that Asian nations have succeeded in this crisis because their citizens are more likely to do as they are told than free-spirited Italians or North Americans.

This idea has uncomfortable echoes of an older, racist debate about so-called “Confucian” cultures, which thinkers like the US political scientist Samuel Huntington described as hierarchical, orderly, and tending to value harmony over competition. As with talk of “Chinese flu” or sudden outbreaks of Sinophobia on American street corners, this line of thinking tells us little about why some countries performed well and others did not.

Preparation is key

Only last October, the Economist Intelligence Unit produced a lengthy report ranking nations by global epidemic preparedness. The US came top, followed by Britain and the Netherlands; Japan and Singapore were 21st and 24th, respectively. However this league table was compiled, it seems to have proved entirely wrong.

Asia has provided many examples of policies that worked—from China’s speedy hospital construction to South Korea’s aggressive testing to Singapore’s contact tracing and open public communication—while in the West, governments that seemed well situated to deliver a swift response have been found wanting.

The thread uniting the countries that did well was that, whether democratic or not, they were strong, technocratically capable states, largely unhampered by partisan divisions. Public health drove politics, rather than the other way around.

Western liberal economies neglected the kind of state capacity in public health and pandemic preparedness that Asian states have quietly been building up.

The truth of this is likely to be cruelly revealed as the virus spreads elsewhere around Asia, and in particular to places like India and sub-Saharan Africa, where state capacity is notoriously weak.

Many such countries have tried to lock down their populations, as the advanced economies did before them. But even if they can slow the virus’s spread, they do not have the benefit of strong health systems, let alone the kind of testing and contact tracing regimes that kept much of Asia safe.

This Asian advantage in competence might not endure into forthcoming phases of the covid-19 crisis, as focus shifts to managing a dramatic economic recession—an area where many Western administrations have recent experience in the wake of the 2008 crash. Governments like those of Britain and the US have already unveiled sizable stimulus packages. But it is undeniable that as they struggled to recover from that financial crisis, Western liberal economies neglected the kind of state capacity in areas like public health and pandemic preparedness that Asian states have quietly been building up. Coronavirus was a test, and the world’s supposedly most advanced nations have all too visibly failed.

All this is damaging to the global reputation of the United States in particular. It was only in 2014 that Barack Obama’s administration managed to lead a global response to an Ebola outbreak in western Africa. Now, six years later, Donald Trump has barely been able to organize a response in his own country.

China is already using this fact to suggest the superiority of its autocratic model of government.

That would be a bad lesson to draw. What matters instead is a new divide between two kinds of countries: those with states that can plan for the long term, act decisively, and invest for the future, and those that cannot.

James Crabtree is an associate professor of practice at the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy at the National University of Singapore. He is author of The Billionaire Raj.

from MIT Technology Review https://ift.tt/2yPUmLV

via IFTTT

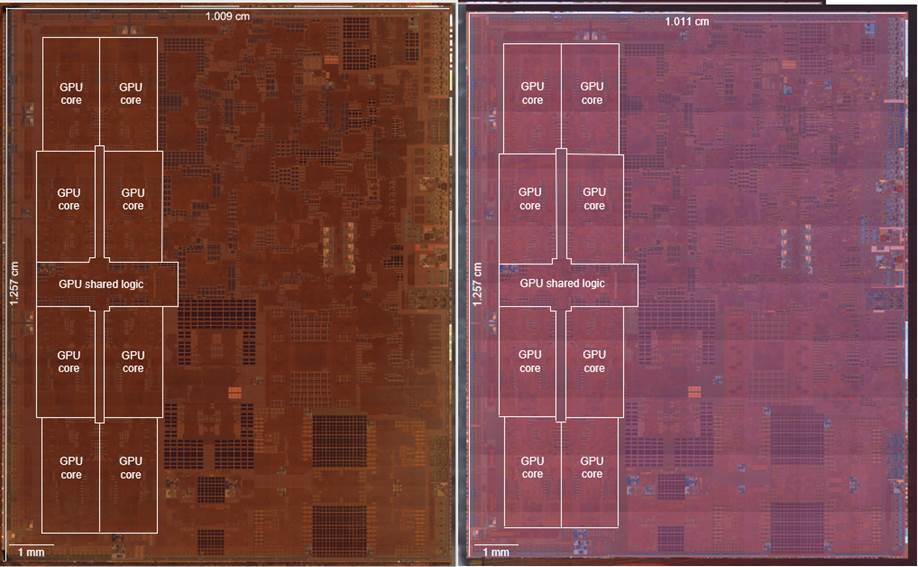

A12Z chip in 2020 iPad Pro confirmed to be an A12X with extra GPU core

The A12Z chip is definitely the same as the A12X.

What you need to know

- The A12Z GPU chip on the iPad Pro has been confirmed to be the same as the A12X.

- The chip was suspected to have been the same when the 2020 iPad Pro launched.

- Techinsights confirmed the similarity of the model today.

Soon after the 2020 iPad Pro was released, it was questioned as to whether the A12Z processor was merely an A12X with an extra GPU core enabled. At the time, a report by NotebookCheck speculated the possibility that Apple had enabled a GPU that had existed but was disabled on the A12X Bionic chip.

"The Apple A12X Bionic has eight physical GPU cores, but one of those cores is disabled. The disabled core is enabled in the new A12Z Bionic that powers the 2020 iPad Pro."

TechInsights had confirmed NotebookCheck's suspicions about the number of cores but had stopped short of saying whether or not the processor was the same, saying that they needed to conduct additional testing.

"Yuzo Fukuzaki, one of TechInsights' Senior Technology Fellows, has confirmed that yes A12X physically has 8 GPU cores. As for the A12Z, we are planning to conduct floorplan analysis to confirm any differences from the A12X."

Today, the outlet has confirmed that the A12Z GPU chip found in the 2020 iPad Pro "is the same as A12X predecessor".

Our analysis confirms #Apple #A12Z GPU chip found inside #iPadPro (model A2068) is the same as A12X predecessor. A report of our findings is underway & will be available as part of TechInsights' #Logic Subscription. Learn more here https://t.co/WWQqlPorNF pic.twitter.com/RsQEADpZsc

— TechInsights (@techinsightsinc) April 13, 2020

Techinsights says that it is compiling a full report of its findings and will be making all of the details available as part of its subscription for paying subscribers.

from iMore - The #1 iPhone, iPad, and iPod touch blog https://ift.tt/2VmfpNQ

via IFTTT

How to clean and sterilize your homemade face mask

from Digital Trends https://ift.tt/3c5D247

via IFTTT

My Long, Unending Journey to Find Perfect Office Equipment

from NYT > Technology https://ift.tt/34mUJJw

via IFTTT

Here's how you'll get Apple and Google's new contact tracing app for your phone - CNET

from CNET https://ift.tt/39ZTuRW

via IFTTT

Ford files a patent application to help sniff out stinky ride-hailing cars - Roadshow

from CNET https://ift.tt/3edIbZL

via IFTTT

Apple's contact tracing system requires verification to report infection

Apple details its COVID-19 reporting function in a press briefing.

What you need to know

- Apple has provided details around the reporting function of its contact tracing systems.

- The company says that reporting yourself as testing positive for COVID-19 will require verification.

- The exact method of verification has not been decided upon yet.

Last week, Apple and Google announced a joint effort to build a contact tracing system into iOS and Android. The system would allow iPhone and Android users to opt-in and receive a notification if they had been in contact with someone who tested positive for COVID-19. Users would also be to report if they tested positive for the virus, alerting others who had been near them in the last fourteen days.

Today, Apple revealed more details about the reporting side of its technology. In a press briefing reported by MacRumors the company said that users who report as having the virus will have to go through a verification process.

At the briefing, Apple explained that users reporting that they have COVID-19 will need to submit proof. This could come in the form of a QR code that is included in the test results, but the exact method has not been decided upon yet.

"As an example, Apple said that a person who tests positive for COVID-19 could receive a QR code with their test results and then scan that QR code within the contact tracing system for confirmation purposes, but the exact implementation remains to be seen. Apple said verification will be handled by an external entity and could vary by region."

The company also reiterated that the entire system will be available to users on an opt-in basis and will not be made mandatory by any government.

A verification process for those reporting as having COVID-19 through the contact tracing system is an important step, as it will ensure false reporting and unnecessary worry is prevented.

from iMore - The #1 iPhone, iPad, and iPod touch blog https://ift.tt/34xGtxO

via IFTTT

eufy Smart Lock Touch with fingerprint recognition launching next month

eufy's first smart lock can unlock your doors with a touch.

What you need to know

- eufy is preparing to launch its first smart lock next month.

- Upcoming lock will feature fingerprint recognition, keypad, and 365 day battery life.

- The eufy Smart Lock Touch will be available for $179.99.

eufy is gearing up for yet another product launch next month, with the latest being a smart door lock. The eufy Smart Lock Touch is the company's first foray into the connected lock market, and it includes several notable features such as fingerprint recognition.

In addition to fingerprint, which is listed as having 0.3 second scan times, the eufy Smart Lock Touch has a digital keypad, app access, and an "original key" which we assume is a physical key. The door lock is completely wireless, providing smart home access via Bluetooth, and is battery powered which is rated for up to 365 days of usage. Rounding out the list of features is an IP65 water resistance rating, a built-in security chip, and auto lock functionality.

Details surrounding voice assistant or smart home integration has not yet been provided, other than it will work with the eufy Security app that is available on both iOS and Android. Current security accessories from the company, such as its smart cameras, support Amazon's Alexa, Google Assistant, and Apple's HomeKit. We have reached out to eufy for some clarification surrounding the lock's compatibility and will update accordingly.

The eufy Smart Lock Touch will be available starting in May with a retail price of $179.99. eufy also plans to release 2 indoor cameras, both of which support HomeKit, and come with an amazingly low price tag, each under $50. eufy also intends to release HomeKit Secure Video support for the eufyCam 2 and 2C sometime in May.

from iMore - The #1 iPhone, iPad, and iPod touch blog https://ift.tt/3caVBUg

via IFTTT

Oumuamua is more likely an interstellar space shard than an alien space ship - CNET

from CNET https://ift.tt/3a9cpJY

via IFTTT

Coronavirus updates: 80 million Americans expected to get stimulus checks this week - CNET

from CNET https://ift.tt/3ekZZ5e

via IFTTT

Coronavirus stimulus check: How to be smart about using your $1,200 - CNET

from CNET https://ift.tt/39Z1jHC

via IFTTT

Denis Villeneuve’s Dune: Everything we know about the movie so far

from Digital Trends https://ift.tt/2BDrsvs

via IFTTT

The fastest cars in the world

from Digital Trends https://ift.tt/2HbkmQp

via IFTTT

8K TV: Everything you need to know about the future of television

from Digital Trends https://ift.tt/2rzCgdf

via IFTTT

Wait, Burning Man is going online-only? What does that even look like?

Android phones will get the COVID-19 tracking updates via Google Play

Illustration by Alex Castro / The Verge

Illustration by Alex Castro / The Verge

Google has confirmed that it will use the Google Play Services infrastructure to update Android phones with the upcoming COVID-19 contact tracing system it is building in collaboration with Apple. It should ensure that more Android phones will actually get the updates, and also ensure that they become available on phones running Android 6.0 Marshmallow or above.

Until today, it was an open question, but one that was vital for Google to answer. That’s because Google Play is the only reliable system that exists for getting software updates pushed out to Android phones in a timely manner. The other way — full operating system updates — is often fraught with delays from both carriers and manufacturers.

Google says that its update system...

from The Verge - All Posts https://ift.tt/3eniXbw

via IFTTT

Reddit will now publicly track political ad spending on its platform

Illustration by Alex Castro / The Verge

Illustration by Alex Castro / The Verge

Reddit is launching a new subreddit that will list all political ad campaigns that have run on the site since January 1st, 2019, the company announced today. The new subreddit can be found at r/RedditPoliticalAds.

“In this community, you will find information on the individual advertiser, their targeting, impressions, and spend on a per-campaign basis,” Reddit said in its announcement post. “We plan to consistently update this subreddit as new political ads run on Reddit, so we can provide transparency into our political advertisers and the conversation their ad(s) inspires.”

Reddit is also updating its policies for political advertising to require political campaigns...

from The Verge - All Posts https://ift.tt/3b8bTgC

via IFTTT