A independent report commissioned by the UK government to examine how competition policy needs to adapt itself for the digital age has concluded that tech giants don’t face adequate competition and the law needs updating to address what it dubs the “novel” challenges of ‘winner takes all’ platforms.

The panel also recommends more policy interventions to actively support startups, including a code of conduct for “the most significant digital platforms”; and measures to foster data portability, open standards and interoperability to help generate competitive momentum for rival innovations.

UK chancellor Philip Hammond announced the competition market review last summer, saying the government was committed to asking “the big questions about how we ensure these new digital markets work for everyone”.

The culmination of the review — a 150-page report, published today, entitled Unlocking digital competition — is the work of the government’s digital competition expert panel which is chaired by former U.S. president Barack Obama’s chief economic advisor, professor Jason Furman.

“The digital sector has created substantial benefits but these have come at the cost of increasing dominance of a few companies which is limiting competition and consumer choice and innovation. Some say this is inevitable or even desirable. I think the UK can do better,” Furman said today in a statement.

In the report the panel writes that it believes competition policy should be “given the tools to tackle new challenges, not radically shifted away from its established basis”.

“In particular, policy should remain based on careful weighing of economic evidence and models,” they suggest, arguing also that “consumer welfare” remains the “appropriate perspective to motivate competition policy” — and rejecting the idea that a completely new approach is needed.

But, crucially, their view of consumer welfare is a broad church, not a narrow price trench — with the report asserting that a consumer welfare basis to competition law is able to also take account of other things, including (but also not limited to) “choice, quality and innovation”.

Furman said the panel, which was established in September 2018, has outlined “a balanced proposal to give people more control over their data, give small businesses more of a chance to enter and thrive, and create more predictability for the large digital companies”.

“These recommendations will deliver an economic boost driven by UK tech start-ups and innovation that will give consumers greater choice and protection,” he argues.

Commenting on the report’s publication, Hammond said: “Competition is fundamental to ensuring the market works in the interest of consumers, but we know some tech giants are still accumulating too much power, preventing smaller businesses from entering the market,” adding that: “The work of Jason Furman and the expert panel is invaluable in ensuring we’re at the forefront of delivering a competitive digital marketplace.”

The chancellor said that the government will “carefully examine” the proposals and respond later this year — with a plan for implementing changes he said are necessary “to ensure our digital markets are competitive and consumers get the level of choice they deserve”.

Pro-startup regulation required

The panel rejects the view — mostly loudly propounded by tech giants and their lobbying vehicles — that competition is thriving online, ergo no competition policy changes are needed.

It also rejects the argument that digital platforms are “natural monopolies” and competition is impossible — dismissing the idea of imposing utility-like regulation, such as in the energy sector.

Instead, the panel writes that it sees “greater competition among digital platforms as not only necessary but also possible — provided the right policies are in place”. The biggest “missing set of policies” are ones that would “actively help foster competition”, it argues in the report’s introduction.

“Instead of just relying on traditional competition tools, the UK should take a forward-looking approach that creates and enforces a clear set of rules to limit anti-competitive actions by the most significant digital platforms while also reducing structural barriers that currently hinder effective competition,” the panel goes on to say, calling for new rules to tackle ‘winner take all’ tech platforms that are based on “generally agreed principles and developed into more specific codes of conduct with the participation of a wide range of stakeholders”.

Coupled with active policy efforts to support startups and scale-ups — by making it easier for consumers to move their data across digital services; pushing for systems to be built around open standards; and for data held by tech giants to be made available for competitors — the suggested reforms would support a system that’s “more flexible, predictable and timely” than the current regime, they assert.

Among the panel’s specific recommendations are a call to set up a new competition unit with expertise in technology, economics and behavioural science, plus the legal powers to back it up.

The panel envisages this unit focusing on giving users more control over their data — to foster platform switching — as well as developing a code of competitive conduct that would apply to the largest platforms. “This would be applied only to particularly powerful companies, those deemed to have ‘strategic market status’, in order to avoid creating new burdens or barriers for smaller firms,” they write.

Another recommendation is to beef up regulators’ existing powers for tackling illegal anti-competitive practices — to make it quicker and simpler to prosecute breaches, with the report highlighting bullying tactics by market leaders as a current problem.

“There is nothing inherently wrong about being a large company or a monopoly and, in fact, in many cases this may reflect efficiencies and benefits for consumers or businesses. But dominant companies have a particular responsibility not to abuse their position by unfairly protecting, extending or exploiting it,” they write. “Existing antitrust enforcement, however, can often be slow, cumbersome, and unpredictable. This can be especially problematic in the fast-moving digital sector.

“That is why we are recommending changes that would enable more use of interim measures to prevent damage to competition while a case is ongoing, and adjusting appeal standards to balance protecting parties’ interests with the need for the competition authority to have usable tools and an appropriate margin of judgement. The goal is to place less reliance on large fines and drawn-out procedures, instead enabling faster action that more directly targets and remedies the problematic behavior.”

The expert panel also says changes to merger rules are required to enable the UK’s Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) to intervene to stop digital mergers that are likely to damage future competition, innovation and consumer choice — saying current decisions are too focused on short-term impacts.

“Over the last 10 years the 5 largest firms have made over 400 acquisitions globally. None has been blocked and very few have had conditions attached to approval, in the UK or elsewhere, or even been scrutinised by competition authorities,” they note.

More priority should be given to reviewing the potential implications of digital mergers, in their view.

Decisions on whether to approve mergers, by the CMA and other authorities, have often focused on short-term impacts. In dynamic digital markets, long-run effects are key to whether a merger will harm competition and consumers. Could the company that is being bought grow into a competitor to the platform? Is the source of its value an innovation that, under alternative ownership, could make the market less concentrated? Is it being bought for access to consumer data that will make the platform harder to challenge? In principle, all of these questions can inform merger decisions within the current, mainstream framework for competition, centred on consumer welfare. There is no need to shift away from this, or implement a blanket presumption against digital mergers, many of which may benefit consumers. Instead, these issues need to be considered more consistently and effectively in practice.

In part the CMA can achieve this through giving a higher priority to merger decisions in digital markets. These cases can be complex, but they affect markets that are critically important to consumers, providing services that shape the digital economy.

In another recommendation which targets the Google-Facebook adtech duopoly, the report also calls for the CMA to launch a formal market study into the digital advertising market — which it notes suffers from a lack of transparency.

The panel also notes similar concerns raised by other recent reviews.

Digital advertising is increasingly driven by the use of consumers’ personal data for targeting. This in turn drives the competitive advantage for platforms able to learn more about more users’ identity, location and preferences. The market operates through a complex chain of advertising technology layers, where subsidiaries of the major platforms compete on opaque terms with third party businesses. This report joins the Cairncross Review and Digital, Culture, Media and Sport Committee in calling for the CMA to use its investigatory capabilities and powers to examine whether actors in these markets are operating appropriately to deliver effective competition and consumer benefit.

The report also calls for new powers to force the largest tech companies to open up to smaller firms by providing access to key data sets, albeit without infringing on individual privacy — citing Open Banking as a “notable” data mobility model that’s up and running.

“Open Banking provides an instructive example of how policy intervention can overcome technical and co-ordination challenges and misaligned incentives by creating an adequately funded body with the teeth to drive development and implementation by the nine largest financial institutions,” it suggests.

The panel urges the UK to engage internationally on the issue of digital regulation, writing that: “Many countries are considering policy changes in this area. The United Kingdom has the opportunity to lead by example, by helping to stimulate a global discussion that is based on the shared premise that competition is beneficial, competition is possible, but that we need to update our policies to protect and expand this competition for the sake of consumers and vibrant, dynamic economies.”

And in just one current example of the considerable chatter now going on around tech + competition, a House of Lords committee this week also recommended public interest tests for proposed tech mergers, and suggested an overarching digital regulator is needed to help plug legislative gaps and work through regulatory overlap.

Discussing the pros and cons of concentration in digital markets, the expert competition panel notes the efficiency and convenience that this dynamic can offer consumers and businesses, as well as potential gains via product innovation.

However the panel also points to what it says can be “substantial downsides” from digital market concentration, including erosion of consumer privacy; barriers to entry and scale for startups; and blocks to wider innovation, which it asserts can “outweigh any static benefits” — writing:

It can raise effective prices for consumers, reduce choice, or impact quality. Even when consumers do not have to pay anything for the service, it might have been that with more competition consumers would have given up less in terms of privacy or might even have been paid for their data. It can be harder for new companies to enter or scale up. Most concerning, it could impede innovation as larger companies have less to fear from new entrants and new entrants have a harder time bringing their products to market — creating a trade-off where the potential dynamic costs of concentration outweigh any static benefits.

The panel takes a clear view that “competition for the market cannot be counted on, by itself, to solve the problems associated with market tipping and ‘winner-takes-most’” — arguing that past regulatory interventions have helped shift market conditions, i.e. by facilitating the technology changes that created new markets and companies which led to dominant tech giants of old being unseated.

So, in other words, the panel believes government action can unlock market disruption — hence the report’s title — and that it’s too simplistic a narrative to claim technological change alone will reset markets.

For example, IBM’s dominance of hardware in the 1960s and early 1970s was rendered less important by the emergence of the PC and software. Microsoft’s dominance of operating systems and browsers gave way to a shift to the internet and an expansion of choice. But these changes were facilitated, in part, by government policy — in particular antitrust cases against these companies, without which the changes may never have happened.

The panel also argues there’s an acceleration of market dominance in the modern digital economy that makes it even more necessary for governments to respond, writing that “network effects and returns to scale of data appear to be even more entrenched and the market seems to have stabilised quickly compared to the much larger degree of churn in the early days of the World Wide Web”.

They also point to the risk of AI and machine learning technology leading to further market concentration, warning that “the companies most able to take advantage of [the next technological revolution] may well be the existing large companies because of the importance of data for the successful use of these tools”.

And while they suggest AI startups might offer a route to a competitive reset, via a substantial technology shift, there’s still currently no relief to be had from entrepreneurial efforts because of “the degree that entrants are acquired by the largest companies – with little or no scrutiny”.

Discussing other difficulties related to regulating big tech, the panel warns of the risk of regulators being “captured by the companies they are regulating”; as well as point out they are generally at a disadvantage vs the high tech innovators they are seeking to rule.

In a concluding chapter considering the possible impacts of their policy recommendations, the panel argues that successful execution of their approach could help foster startup innovation across a range of sectors and services.

“Across digital markets, implementing the recommendations will enable more new companies to turn innovative ideas into great new services and profitable businesses,” they suggest. “Some will continue to be acquired by large platforms, where that is the best route to bring new technology to a large group of users. Others will grow and operate alongside the large platforms. Digital services will be more diverse, more dynamic, with more specialisation and choice available for consumers wanting it. This could drive a flourishing of investment in these UK businesses.”

Citing some “potential examples” of services that could evolve in this more supportively competitive environment they suggest social content aggregators might arise that “bring together the best material from people’s friends across different platforms and sites”; “privacy services could give consumers a single simple place to manage the information they share across different platforms”; and also envisage independent ad tech businesses and changed market dynamics that can “rebalance the share of advertising revenue back towards publishers”.

The main envisaged benefits for consumers boil down to greater service and feature choice; enhanced privacy and transparency; and genuine control over the services they use and how they want to use them.

While for startups and scale-ups the panel sees open standards and access to data — and indeed effective enforcement, by the new digital markets unit — creating “a wide range of opportunities to develop and serve new markets adjacent to or interconnected with existing digital platforms”.

The combined impact should be to strengthen and deepen the competitive digital ecosystem, they believe.

Another envisaged benefit for startups is “trust in the framework and recognition that promising, innovative digital businesses will be protected from foreclosure or exclusion” — which they argue “should catalyse investment in UK digital businesses, driving the sector’s growth”.

“The changes to competition law… mean that where a business can grow into a successful competitor, that route to further growth is protected and companies will not in the future see being subsumed into a dominant platform as the only realistic business model,” they add.

via Startups – TechCrunch https://ift.tt/2u2qCWH

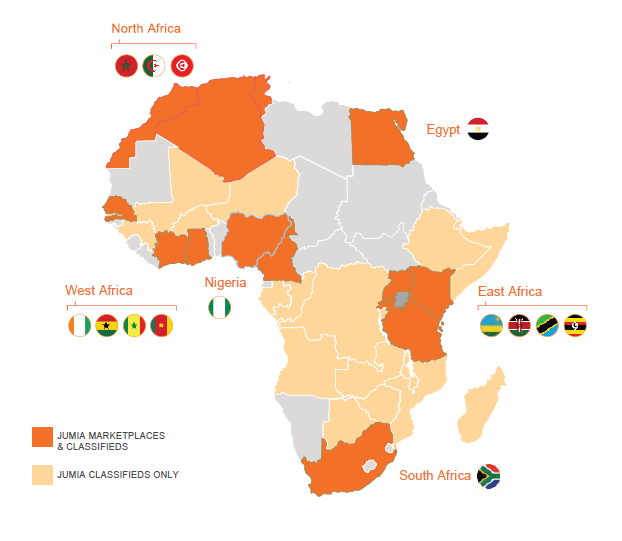

Starting in Nigeria, the company created many of the components for its digital sales operations. This includes its JumiaPay payment platform and a delivery service of trucks and motorbikes that have become ubiquitous with the Lagos landscape.

Starting in Nigeria, the company created many of the components for its digital sales operations. This includes its JumiaPay payment platform and a delivery service of trucks and motorbikes that have become ubiquitous with the Lagos landscape. In late 2018, Nigerian online sales platform

In late 2018, Nigerian online sales platform